|

A

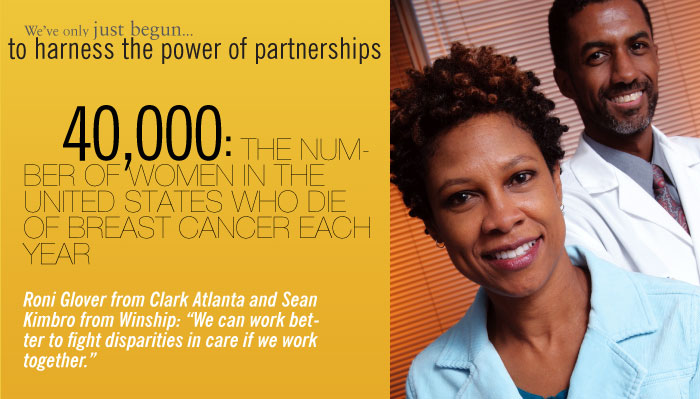

DISPROPORTIONATE NUMBER OF THE ABOVE TOTAL ARE AFRICAN AMERICAN, AND RONI

GLOVER, A GRADUATE STUDENT AT CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY, IS WORKING WITH

THE WINSHIP CANCER INSTITUTE TO FIND OUT WHY.

“When patients first hear the words

‘you have cancer,’ they are overwhelmed—they don’t

absorb much else that the doctor may be trying to get across during the

rest of the conversation,” says Glover, who is analyzing reasons for

the prolonged time between diagnosis and the beginning of treatment in African

American patients as part of her work for her PhD in health care social

work.

To do her research, Glover

needed access to patients, clinicians, and other social workers in cancer.

Helping her build this network and serving as her mentor is Sean Kimbro,

a molecular biologist recruited to Emory from Clark Atlanta to serve as

program director of the Georgia Center for Health Equality, a coalition

of hospitals and universities led by Winship with a $3.7 million grant from

the National Institutes of Health.

Kimbro’s own research focuses on why

a particularly aggressive form of breast cancer disproportionately affects

young African American women, regardless of issues such as socioeconomic

status or access to care. But he understands the importance of these social

issues in the health care disparities equation. “It was Sean who brought

behavioral scientists on our research team,” says Glover. In addition,

she says, he “pointed out angles I hadn’t thought of”

and connected her with people throughout Winship who could help her.

This scenario repeats itself with other students

at Clark Atlanta and Morehouse School of Medicine, the other two schools,

in addition to Emory and the Grady Health System, involved in the Georgia

Center for Health Equality. The center is dedicated to training minority

graduate students in health-related areas and to counteracting lack of knowledge,

lack of access, and other barriers that lead to disparities in care.

“From my perspective, what’s important

about this center is that it’s bridging the communications gap between

Emory and these other institutions,” says Kimbro. “We can work

better if we work together, and it’s bringing us all together to address

a common cause.” |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Fighting

a triple negative |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

When doctors analyze breast tumors, they look for obvious vulnerabilities.

If they know which substance(s) make a tumor grow, they can

block these and thus deprive the tumor of what it craves. Some

of the most deadly breast tumors are those that respond to none

of the three more well-known targets (estrogen, progesterone, or HER-2/neu) and therefore to none

of the treatment strategies leveled against them. “Triple-negative”

breast cancer tends to strike younger women, and particularly,

younger African American women. There is precious little

data about the molecular profile of such tumors in this population

and thus little on which to base screening or new targets for

treatment. Winship researcher Mary Jo Lund hopes to change that

by establishing a repository of tumor specimens from all women

newly diagnosed with breast cancer in Fulton and DeKalb counties,

where 20% of all breast cancers in Georgia are diagnosed. Black

female residents of these counties account for 38% of all newly

diagnosed invasive breast cancers, and an inordinately large

proportion of these women are under 50 when diagnosed (42% compared

with 26% of white women). “We hope to use this data to

improve outcomes for all women with breast cancer, particularly

the underserved,” says Lund.

(estrogen, progesterone, or HER-2/neu) and therefore to none

of the treatment strategies leveled against them. “Triple-negative”

breast cancer tends to strike younger women, and particularly,

younger African American women. There is precious little

data about the molecular profile of such tumors in this population

and thus little on which to base screening or new targets for

treatment. Winship researcher Mary Jo Lund hopes to change that

by establishing a repository of tumor specimens from all women

newly diagnosed with breast cancer in Fulton and DeKalb counties,

where 20% of all breast cancers in Georgia are diagnosed. Black

female residents of these counties account for 38% of all newly

diagnosed invasive breast cancers, and an inordinately large

proportion of these women are under 50 when diagnosed (42% compared

with 26% of white women). “We hope to use this data to

improve outcomes for all women with breast cancer, particularly

the underserved,” says Lund. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Harness

the power of partnerships: |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

>

GATHER MISSING PIECES OF THE PUZZLE. Winship is building a team

of experts in various fields, from nanotechnology to molecular

biology and epidemiology, to tease out genetic differences in

breast tumor samples. A gift of $25,000 can pay for equipment

and technical assistance needed in this effort to help devise

new strategies against one of the most deadly types of tumor,

which is found more frequently in African Americans. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

>

EASE THE BURDEN OF CENCER. The Patient and Family Resource Center

at the Winship Cancer Institute provides support for patients

and their families while they are undergoing treatment. Each

family’s needs are as different as each donor’s

ability to give. A $100 gift helps provide snacks for support

groups. Gifts of $1,000 strengthen the center’s emergency

resource fund to pay for prescriptions for patients whose money

has run out. Funding a caregiver’s cancer support group

can be done for only $2,500. And a naming opportunity at $2

million for the center would help the center help more people.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

>

SUPPORT CLINICAL TRIALS. Because of their complexity and size,

these are among the most expensive components of cancer research.

A $100,000 gift can go a long way in helping move a new drug

through the long process to approval. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Send

your gift today by calling 404-727-3518, or give

online. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

(estrogen, progesterone, or HER-2/neu) and therefore to none

of the treatment strategies leveled against them. “Triple-negative”

breast cancer tends to strike younger women, and particularly,

younger African American women. There is precious little

data about the molecular profile of such tumors in this population

and thus little on which to base screening or new targets for

treatment. Winship researcher Mary Jo Lund hopes to change that

by establishing a repository of tumor specimens from all women

newly diagnosed with breast cancer in Fulton and DeKalb counties,

where 20% of all breast cancers in Georgia are diagnosed. Black

female residents of these counties account for 38% of all newly

diagnosed invasive breast cancers, and an inordinately large

proportion of these women are under 50 when diagnosed (42% compared

with 26% of white women). “We hope to use this data to

improve outcomes for all women with breast cancer, particularly

the underserved,” says Lund.

(estrogen, progesterone, or HER-2/neu) and therefore to none

of the treatment strategies leveled against them. “Triple-negative”

breast cancer tends to strike younger women, and particularly,

younger African American women. There is precious little

data about the molecular profile of such tumors in this population

and thus little on which to base screening or new targets for

treatment. Winship researcher Mary Jo Lund hopes to change that

by establishing a repository of tumor specimens from all women

newly diagnosed with breast cancer in Fulton and DeKalb counties,

where 20% of all breast cancers in Georgia are diagnosed. Black

female residents of these counties account for 38% of all newly

diagnosed invasive breast cancers, and an inordinately large

proportion of these women are under 50 when diagnosed (42% compared

with 26% of white women). “We hope to use this data to

improve outcomes for all women with breast cancer, particularly

the underserved,” says Lund.