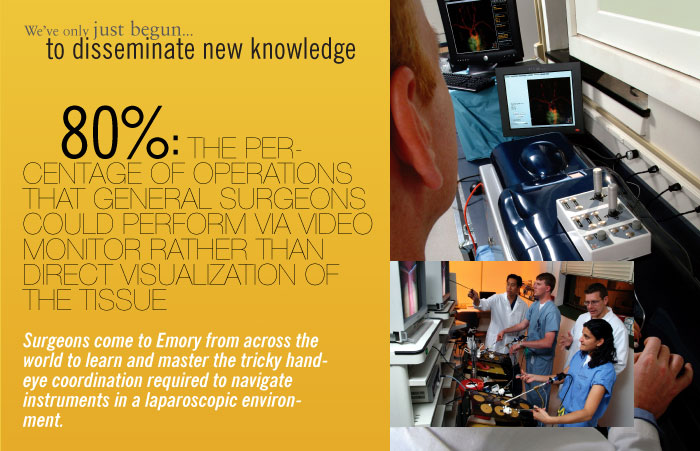

Surgical procedures increasingly are performed via videoscopy with customized instruments and tiny cameras placed through incisions far too small to admit a surgeon’s hand. The surgical team “sees” the tissue being operated on through two-dimensional images on an overhead

television monitor, and remotely controlled surgical robots provide greater

precision than ever possible with the human hand alone. In

the future, the surgeon can operate with exacting care on what appears on

the monitor to be a motionless heart or brain tumor or pancreas while

the robot monitors heart rate, breathing, and other movement and corrects

placement of the instrumentation.

television monitor, and remotely controlled surgical robots provide greater

precision than ever possible with the human hand alone. In

the future, the surgeon can operate with exacting care on what appears on

the monitor to be a motionless heart or brain tumor or pancreas while

the robot monitors heart rate, breathing, and other movement and corrects

placement of the instrumentation. The Emory Simulation, Training and Robotics (ESTAR) program headed by Smith has made Emory one of the leading schools in the nation for teaching surgical procedures via simulation and for research validating this innovative type of training.

Surgeons come to Emory from across the world to learn and master the tricky hand-eye coordination required to navigate instruments in a laparoscopic environment. Soon, Emory will be “going home” with many of them. Surgeons who learn new procedures at ESTAR can continue their simulation training back in their own institutions, while Emory faculty monitor their progress over the Internet. When the surgeons are ready to perform a new procedure for the first time on a real patient, an Emory surgeon will use Internet-connected robots to be virtually present in the operating room, wherever in the world that may be.

| Next

chapter: to explore hidden connections>> |

||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright

© Emory University, 2006. All Rights Reserved

satisfaction as the stone explodes into powder. If this

were a video game, the score would read Accurate! Cured!

Studies show that training on a simulator makes surgeons better

at operating simulators, says Emory’s Ken Ogan. But the

real goal is to reduce the learning curve and improve skills

in the operating room. To evaluate this teaching technology,

Ogan is using the uro-mentor to teach Emory urology residents

to treat kidney stones. Their performance during actual procedures

in the OR will then be compared with that of residents trained

via traditional methods. Bottom line, he says, the hope is that

the virtual reality training will improve patient care and reduce

cost and complications.

satisfaction as the stone explodes into powder. If this

were a video game, the score would read Accurate! Cured!

Studies show that training on a simulator makes surgeons better

at operating simulators, says Emory’s Ken Ogan. But the

real goal is to reduce the learning curve and improve skills

in the operating room. To evaluate this teaching technology,

Ogan is using the uro-mentor to teach Emory urology residents

to treat kidney stones. Their performance during actual procedures

in the OR will then be compared with that of residents trained

via traditional methods. Bottom line, he says, the hope is that

the virtual reality training will improve patient care and reduce

cost and complications.