|

In Brief

|

Nobel citizen of a troubled world

On December 10, 2002, in Oslo, President James Earl Carter Jr. was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace. William

Foege, Presidential Distinguished Professor of International Health and longtime Carter friend, was among

those packed in the town hall to witness the landmark event. These are his firsthand observations of the

moving ceremony, highlighted by Jesse Norman’s rendition of “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” and by

President Carter’s address.

|

|

|

“President Carter was part of the chain of 90 people, going back 101 years, recognized for their roles in

improving the understanding of peace. His life was in the talk as he defined himself as a ‘citizen of a

troubled world,’ but then he went on to say that ‘individuals are not swept along on a tide of inevitability.’

This is not a fatalistic world. He and Mrs. Carter have lived the belief that individuals can make this a

better world. And that is exactly what they have done.”

In his Nobel Prize speech, President Carter identified “a growing chasm between the richest and poorest people

on earth” as the greatest challenge faced by the world. “The identification of the gap between rich and poor

as the prime world problem is right on,” Foege says, “and it carries a profound public health message. Equity

must be the objective.”

Foege equally enjoyed a live one-hour CNN interview of President Carter by Jonathan Mann a few hours after the

ceremony. “President Carter was as good as I have seen him, with common sense answers,” Foege says. He

particularly remembers the answer to the question, “Why do you work with rogues?” Without missing a beat,

President Carter answered, “Because they are the ones causing the problems.”

|

|

“At the beginning of this new millennium, I was asked to discuss here in Oslo the greatest challenge that the

world faces. Among all the possible choices, I decided that the most

serious and universal problem is the growing chasm between the richest and poorest people on earth. Citizens

of the 10 wealthiest countries are now 75 times richer than those who live in the 10 poorest ones, and the

separation is increasing every year, not only between nations but also within them. The results of this

disparity are root causes of most of the world’s unresolved problems, including starvation, illiteracy,

environmental degradation, violent conflict, and unnecessary illnesses that range from Guinea worm to

HIV/AIDS.”

–President Jimmy Carter, 2002 Nobel address

|

Building bridges for mental health

Benjamin Druss is quick to point out the reasons he decided to accept the Rosalynn Carter Chair of Mental

Health. “This is the very first endowed chair of mental health at a school of public health in the country.

The fact that the chair is based in a school of public health in a department of health policy fits well with

my long-standing interest in mental health policy. And the link with The Carter Center provides a natural

alliance between research and action.”

| This chair is the first joint appointment between the Rollins School of Public Health (RSPH)

and The Carter Center. Former First Lady Rosalynn Carter, who founded The Carter Center Mental Health Task

Force, is looking forward to working with Druss, who will serve as associate professor of health policy at

RSPH.

“Mental illnesses have been neglected for too long in the public health arena,” she says. This chair “will

bring national recognition and attention to the promotion of mental health and prevention of mental

disabilities.”

|

|

As the first Rosalynn Carter Chair of Mental Health, Druss sees his role at Emory as a bridge builder between

the components of mental health both on and off campus.

|

Druss contributes a broad background to this new effort, having worked both as a clinician and health services

researcher. With an MD from New York University and an MPH from Yale, he has trained as a resident in internal

medicine at Brown University and in psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine. In addition to board-certification

in psychiatry, he has completed an NIMH-funded health services research fellowship, an experience he describes

as formative. Druss comes to Emory from Yale, where he held appointments in the departments of psychiatry and

public health and directed the Program in Mental Health Policy Studies.

Currently, Druss serves on the Institute of Medicine’s Committee on Identifying Priority Areas for Quality

Improvement, and he is a consultant to some of the country’s most influential mental health groups, including

the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, the NIMH, the Robert Wood Johnson Program on

Depression in Primary Care, and the National Center for Quality Assurance. He is a recipient of the American

Psychiatric Association Early Career Health Services Research Award and the Association for Health Services

Research Article-of-the-Year Award.

At Emory, Druss hopes to build on the portfolio of work that includes initiatives to improve primary medical

care for patients with serious mental disorders. He sees his role at Emory as a bridge builder between the

components of mental health both on and off campus. At the RSPH, he plans to increase the presence and

awareness of mental health issues as a part of the larger public health system. In Emory Medical School’s

Department of Psychiatry, he hopes to support clinical researchers in discovering the real-world applications

of their work. And at The Carter Center, he wants to help provide the research evidence that can then be used

for action-oriented policies and programs.

“After all,” Druss says, “health services research is by nature a field that you can't disentangle from

the real world.”

Ruth Berkelman |

|

"Threats we can do something about"

Ruth Berkelman could tell you things you don’t want to know: about potential designer diseases, for

example, with genetically manipulated pathogens that create new, unknown terrors—say a gene from ebola

inserted into the smallpox virus. Or biological weapons, the poor man’s nuclear arsenal, which are easily

hidden and portable, with an ability to multiply exponentially. Or dirty bombs released to cause widespread

contamination.

As head of the Center for Public Health Preparedness and Research (CPHPR), Berkelman can also tell you the

best way to take away some of the anxiety. “We have to focus on the threats that we can do something about,”

she told an audience at an Emory Board of Visitors lunch held at the Rollins School of Public Health in

January. “A strong public health system is the best underpinning for dealing with a terrorist threat.

Knowledge is a good thing. It helps take away some of the terror.” |

During her lecture, Berkelman—Rollins Professor of Public Health Preparedness and an internationally

recognized expert in emerging infectious diseases and disease surveillance—shared some of the projects the

CPHPR has undertaken. Established in January 2002, the CPHPR seeks to prepare public health professionals and

the community to address emerging infectious diseases and potential bioterrorist threats. The center conducts

research on the capacity of public health systems to detect and respond to infectious disease threats. It

equips Georgia public health professionals with skills to combat terrorist attacks in collaboration with the

state’s Division of Public Health. And it assists public health departments at the federal, state, and local

level in planning and implementing effective health risk and crisis communication programs.

One important initiative of the CPHPR is the Triangle Lecture Series that brings together public health

officials, clinicians, and university researchers from throughout metro Atlanta each month. Through the

evening lecture series, the key people in public health are having an opportunity to meet and interact with

each other before a crisis. The center is making another contribution in the area of graduate education with

two new courses at the RSPH: Public Health Preparedness and Bioterrorism, and Crisis Communication and Public

Health.

“The level of the threat of bioterrorism is debated, as is the potential impact of a bioterrorist attack,”

says Berkelman. “There is consensus, however, that the level of a threat is increasing.” The CPHPR is

strengthening the public health system to insure our nation and our communities are prepared and ready to

respond.

It's the Law

A new book seeks to explain the law of public health practice to people with limited or no background in law.

With 20 chapters that range from criminal law to vaccination mandates,

The Law in Public Health Practice provides a

thorough examination of the legal basis of public health practice and covers emerging areas where law and

public health intersect. CDC’s Richard Goodman, an adjunct professor at the Rollins School of Public Health,

is co-editor of the volume, and Professor of Epidemiology James Buehler is a contributor.

|

Storing vaccines, safely

The success of an immunization program depends not only on the number of people who are vaccinated but also on

the effectiveness of the vaccine. Yet, according to the World Health Organization, most live vaccines can

survive at room temperature for only short periods of time. Failure to adhere to handling and storage

recommendations can reduce or destroy the vaccine’s effectiveness.

A pilot study of vaccine storage practices in primary care physician’s offices nationwide has led to a major

quality management and patient safety initiative by Aetna, one of the nation’s leading providers of health

care and related group benefits. Julie Gazmararian, professor of Health Policy and Management for the Emory

Center on Health Outcomes and Quality, conducted the pilot, which focused on four cities: Detroit,

Jacksonville, Phoenix, and Las Vegas, and results appeared in the American Journal of Preventive

Medicine. |

|

Julie Gazmararian |

Based on the results of the pilot study, Aetna launched the Vaccine Safe Storage Project in 5,300 offices of

primary care physicians—a major distribution channel for vaccines. The project, funded by GlaxoSmith-Kline,

aimed to improve compliance with vaccine storage guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) and included an initial survey of storage procedures, education materials, tools to support

safe vaccine storage, and a follow-up survey. Following the project, improvement in physician compliance with

CDC’s safe storage guidelines ranged from 2% to 20%.

Gazmararian noted a 10% improvement in physician offices having a thermometer in refrigerators where vaccines

were stored to assess and record temperatures. Storage of vaccines in the refrigerator door (where

temperatures frequently are less stable) decreased by 13%, and storage in the freezer door decreased by 2%.

The use of a temperature log to record and track temperatures daily increased by 18% for refrigerators and 13%

for freezers.

“The study is an excellent example of how a national managed care organization can effectively address an

important safety issue,” Gazmararian says. “By providing important information to the provider offices, we

were able to make a difference in how vaccines are stored.”

Vaccine storage practices in primary

care physician offices - Assessment and intervention,

American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Volume 23, Issue 4 , November 2002, Pages 246-253.

Unintended pregnancies cut across class lines

Accidental pregnancy and poverty may be the stereotype, but the reality of unintended pregnancy cuts across

social and economic lines, according to a new study by researchers at the Emory Center on Health Outcomes and

Quality. Published in the Maternal and Child Health Journal, the study examined a population of women

who were married, educated, and had incomes of more than $40,000. Almost one-third of births in the study

period resulted from an unintended pregnancy.

“Traditionally, attention has been focused on unintended pregnancies in disadvantaged populations, but few

studies have focused on women in more affluent, lower-risk groups,” says Diane Green, the lead investigator

and a faculty member in Health Policy. “These data show that the same issues are in play even for women with

higher education levels and more financial resources.”

Conducted with data from a managed care organization that operates nationwide, the study compares

socio-demographic factors, pregnancy history, and elements of contraceptive use between women with intended

and unintended pregnancies. When examining contraceptive use among the women in the study, researchers found

that only 40% of the women with unintended pregnancies reported using contraception. Of that group, two-thirds

were using barrier methods such as condoms and diaphragms—less effective than hormonal methods of

contraception.

Green believes a variety of organizations involved in family planning or health care can help reduce the rate

of unintended pregnancy. Health care systems, including clinicians and health educators, can provide improved

education on proper contraceptive use as well as promote consistent use of contraception.

Predicting paths of epidemics

Ira Longini |

|

In November, biostatistician Ira Longini presented his work on predicting the paths of epidemics for Emory’s

Great Teacher’s lecture series. Longini—an expert in the statistical modeling of infectious diseases—finds

mathematical answers to questions about epidemics, from influenza to HIV/AIDS to smallpox: How efficacious are

flu vaccines? How will an HIV vaccine protect people and who should get it? Would mass or targeted

vaccinations for smallpox best contain a bioterrorist attack? The infectious diseases Longini studies pose

serious threats to public health. Smallpox, for instance, was the cause of 500 million deaths in the 20th

century alone. A total of 20 million people have died of AIDS, with another 40 million currently infected

worldwide. During his lecture, Longini calculated that another 570 new infections of HIV had occurred.

|

Docs with a public health bent

Jeremy Hess and Jill Jarrell wanted more than a traditional medical education. When they began considering

their educational possibilities, they each sought medical schools that incorporated studies in public health

with medicine. In Emory’s MD/MPH program, they found a good match. Now, as they end five years of coursework

(four in medicine and one in public health), Hess and Jarrell value their decision more than ever.

“Human health involves more than just science,” says Jarrell. “I believe every medical student or doctor

should get an MPH.”

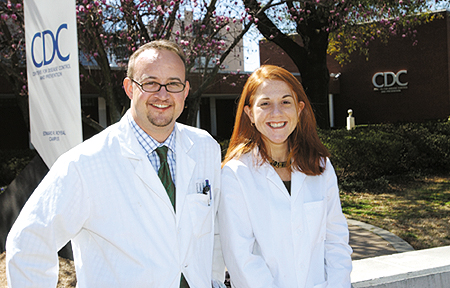

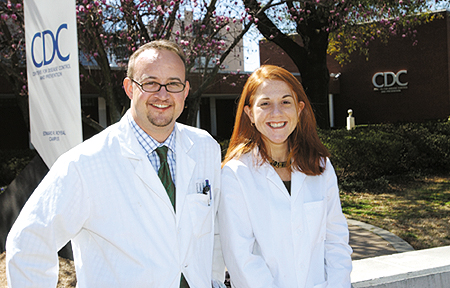

MD/MPH students Jeremy Hess and Jill Jarrell are the first recipients of O.C. Hubert EIS 50th Anniversary

Fellowships, which allow them to participate in an applied epidemiology rotation at the CDC.

|

Hess and Jarrell are the first two recipients of O.C. Hubert EIS 50th Anniversary Fellowships. These

fellowships—made possible by a grant from the Hubert family to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC) Foundation—provide support for students to participate in an elective rotation at CDC in applied

epidemiology, under the guidance of the Epidemic Intelligence Service.

The elective gives fellows an opportunity to work to contain or study infectious disease outbreaks and to

participate in epidemiologic investigations in areas such as cancer, chronic diseases, and environmental and

occupational diseases.

During his recent elective, Hess headed to a mining town in Nevada to follow up on an investigation that

showed elevated levels of tungsten in a cluster of patients with leukemia. The question the CDC team wanted to

answer was whether levels of tungsten were as high in people who live in other parts of Nevada as they were in

the cluster patients. If elevated levels of tungsten exist throughout Nevada’s population, then a correlation

with leukemia incidence is less likely. However, if the tungsten levels differ significantly in the control

group, then the researchers may be able to pinpoint a relation between tungsten and leukemia.

“It was great to see how a field study is conceptualized and executed,” says Hess, “and how all the different

factors––outcome measures, study design, and logistics planning––have to come together on the fly.”

The CDC rotation builds on Hess’s growing portfolio of experience in public health at home and abroad. For

example, he helped establish HIV/AIDS prevention programs in the Philippines, Thailand, and in Rhode Island.

Last summer, he worked with CARE in Rwanda to evaluate the effectiveness of a food aid program to households

headed by children, who were orphaned due to either AIDS or the genocide. After completing a residency in

emergency medicine, Hess hopes to take his experience in medicine and public health to the international

health arena.

Jarrell likewise hopes to bring aspects of public health to medical practice, either as an academic researcher

or as a medical missionary. “I want to practice a brand of medicine deeply rooted in service,” says Jarrell.

Her classes in health policy and management ignited a particular interest in advocating for universal health

care and the effective allocation of resources in the health care system—touchstones for her future career.

“The MD/MPH program recruits the best candidates,” says epidemiologist John McGowan, himself a medical doctor

and public health practitioner. The program often draws some of Emory’s most prestigious scholarship holders,

including Robert W. Woodruff scholars like Hess. Next year, three Woodruff scholars––including recent

Humanitarian Award winner Nishant Shah––will follow in Hess’s and Jarrell’s footsteps, combining public health

and medicine to become what Jarrell calls “more holistic physicians.”

Woodruff Scholar and MD/MPH student

| Nishant Shah (center) was one of seven Emory Humanitarian Award winners

announced this January. As an undergraduate of Emory College, Shah volunteered to tutor refugee children in

Clarkston, Georgia, and served in the Catholic Social Services Refugee Family Friends Program, teaching adult

English. |

|

|

He also tutored Bosnian children after school through All Saints Episcopal Church and did additional

volunteer work on behalf of Bosnian refugees. After graduating with a 3.9 GPA with degrees in anthropology and

human biology, Shah spent almost a year in Cambodia, where he helped develop management tools and nutrition

education programs at the Angkor Hospital for Children.

During medical school, he has participated in significant political action groups to improve the health care

of those who are underserved, according to Executive Associate Dean of Medicine Jack Shulman, who nominated

Shah. A leader of Physicians for Social Responsibility, Shah helped organize a student group interested in

alternative medicine, and he volunteers frequently at the Open Door Community Health Clinic. For the past

seven years, students from the RSPH have been among those selected campus-wide to receive Emory's Humanitarian

awards.

Spring 2003 Issue |

Dean's Message |

The Legacy of Childhood Nutrition |

Strong Partners

This News Could Save Your Life |

An idea, of SORTS |

Class Notes

Rollins School of Public Health

Copyright © Emory University, 2003. All Rights

Reserved.

Send comments to

hsnews@emory.edu.

|