|

|

| |

|

|

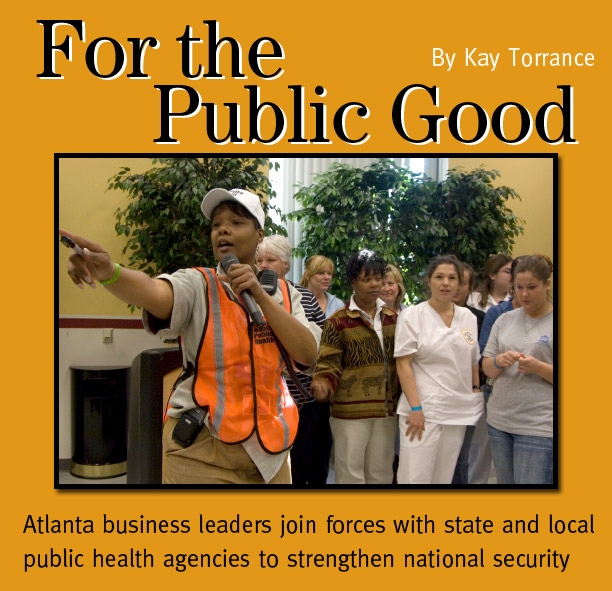

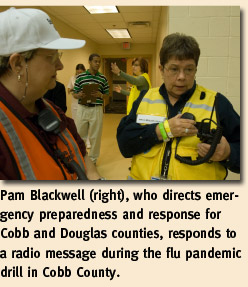

A volunteer instructs participants from the Atlanta business and public health communities during a flu pandemic drill in Cobb County. |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Business and public health historically have been like oil and water; they just didn't mix. Many company executives and public health officials viewed each other with caution at best or suspicion at worst. Common thinking was: Government efforts to protect public health often result in cumbersome regulations, or business is always trying to make a buck, regardless of the greater impact. But the events of fall 2001—the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon and anthrax-laced mailings to government offices and media companies—set the two sides on a common path. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

These events directly affected workers. Looking back to lessons learned, state and federal officials realized that private businesses should be included in response plans to any large-scale emergency. In the event of a natural disaster, pandemic flu, or bioterrorist attack, businesses can often perform certain functions more efficiently and effectively. They can tap supplies, storage facilities, vehicles for distribution, and communications links, while government agencies, including public health departments, can lead a response and provide access to antibiotics and vaccines. In other words, public health and the private sector need each other. Neither could respond successfully to a crisis alone.

The Metro Atlanta Region of Business Executives for National Security (BENS)—a nonprofit group of business leaders dedicated to improving the country's security—reached out to the CDC before 2001 and to state and local public safety and public health leaders following the anthrax attacks in 2001. BENS leaders asked: How can we help? the anthrax attacks in 2001. BENS leaders asked: How can we help?

Through participation in Georgia's Homeland Security Task Force, BENS formed an innovative partnership with state and local health officials in DeKalb, Cobb, and Douglas counties and the Rollins School of Public Health (RSPH) to show how they can team up to dispense medication during a public health emergency. The collaboration will help improve the state's ability to respond to a public health crisis.

"There's a growing body of evidence that we must have business–public health collaboration," say Ruth Berkelman, professor of epidemiology in the RSPH.

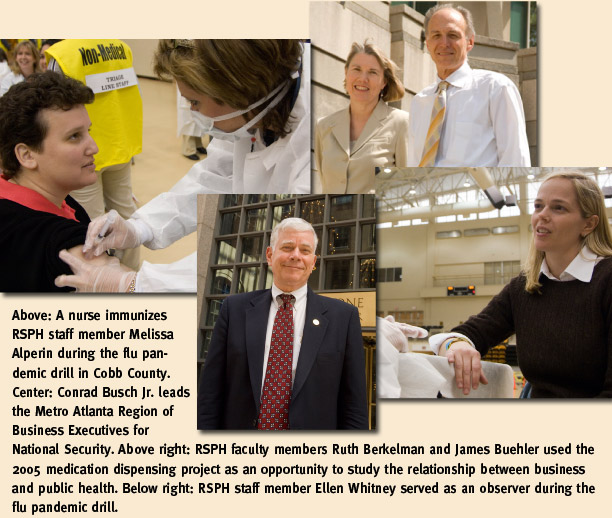

In 2004, Berkelman met Conrad Busch Jr., director of metro Atlanta BENS, at a policy forum and watched the business–public health relationship develop through subsequent meetings. Both thought studying the relationships developed during the dispensing–medication project would be beneficial, as there is little research in the growing field of emergency preparedness.

Berkelman, who directs the Center for Public Health Preparedness and Research at the RSPH, was joined by James Buehler, RSPH research professor and the study's lead investigator, and Ellen Whitney, associate director of research projects for the center, to study these relationships, with support from the Sloan Foundation. After the project's completion, the researchers interviewed participants from BENS, Georgia's Division of Public Health, and participating local health departments to gauge lessons learned from the collaboration and how to cement a dispensing plan of action. The results were published in the November 20, 2006, issue of BMC Public Health. What was learned could prove to be a valuable resource for Georgia and other states in planning for their security. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Planning for the worst

Following the anthrax attacks in 2001, BENS and the state began thinking about how antibiotics or vaccines would be distributed to Georgians in the event of a local or regional bioterrorism attack. The CDC maintains a cache of medications and supplies in various secret locations around the country for such an event, and it can move the Strategic National Stockpile to states within hours. States then must distribute medications and supplies to their citizens. In the event of a bioterrorist anthrax attack, the CDC has mandated that health departments dispense post-exposure antibiotics within 48 hours. That adds up to a daunting logistic challenge, especially if medication is required for hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people.

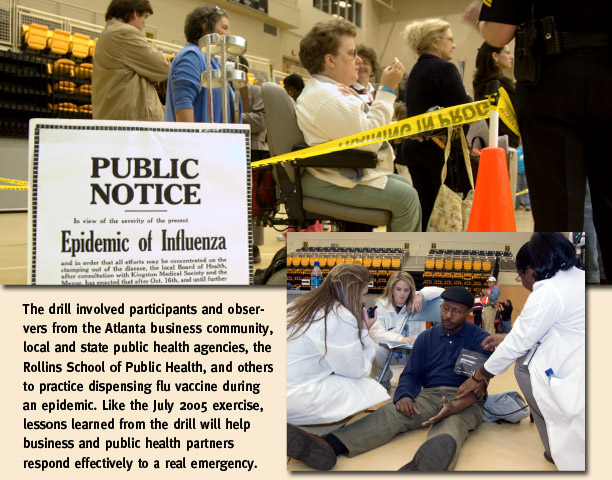

After working on a game plan for several years, BENS and state officials decided to test it in July 2005 in a live exercise. BENS members recruited 1,200 volunteers from their companies to serve as mock patients following a hypothetical bioterrorist attack and as observers to record the exercise. An undisclosed company site was used in Cobb County. Company volunteers ran that site, with public health oversight, to learn how to perform dispensing tasks. Public health officials spearheaded two additional sites, using schools in metro Atlanta.

"Instead of having a site completely managed by public health representatives, most of the common tasks—signage, filling out forms, managing the lines—can be taken care of by business employees," Busch says. "Public health can save its labor for other locations."

The corporate dispensing site was designed to first serve company employees and their families. In the case of a real attack, this would allow companies to remain in business to serve the community and enable medicated business employees to serve as volunteers at public health dispensing sites.

"Not only do you want to stay in business for self-serving reasons, but business continuity is critical for the economy and the country, especially if you are a business critical to the area's infrastructure—a gas or energy provider or a bank, for example," Busch says.

The exercise allowed BENS and state health officials to see what problems arose that hadn't been addressed in their original plan. How were they going to organize the flow of people through dispensing sites? Would people have to be bused in or would they be able to park at the site? If an attack occurred during the hottest days of summer, would buses without air-conditioning pose a health hazard to young children and the elderly?

Based on insights gained from the 2005 exercise and other public health exercises, planning is now under way throughout metro Atlanta to expand business and public health collaboration in developing capacity for emergency mass dispensing. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Changing perceptions

Perhaps more than fine-tuning logistics, researchers found the most commonly cited challenge to the partnership was the difference in culture. As one public health official in the study says, "Public health and business people speak a different language. Business people. . .focus on measurable outcomes based on dollars. Public health people are [concerned about the] well-being of humanity, but you can't reduce that to dollars."

"We described how business and public health cultures are different," says Buehler. "The more people from different cultures work together, the more they respect each other. The initial distrust lessens. It's everybody's goal to have community continuity."

The differences seemed to be based on a lack of knowledge about each other's resources and management styles. Going into the exercise planning, members from both sides had preconceived notions about the other. Public health representatives wondered, "What is this guy trying to sell me?" Business leaders viewed government officials as inefficient, hampered by a bureaucratic mind-set.

While BENS and state health officials say there are still kinks in the dispensing plan, both sides say the collaboration has proven successful, and a response to a public health emergency today would be much better than just a few years ago. The partnership succeeded in building a bridge between business and public health in order to work together effectively in the future. "The bottom line is trust, and we have it," Busch says.

J. Patrick O'Neal, medical director of Georgia's Office of Emergency Medical Services, agrees that the partnership has evolved. "The relationship between public health and the business community has moved from a position of interest but with considerable wariness to one of respect for a common goal of community preservation albeit from different motivations," he says.

As one participant told the researchers, "It has taken five or more years to move from casual ‘handshake' relationships to one where people are on one another's speed dials. Relationship building cannot be rushed."

Kay Torrance is an editor and writer in the Woodruff Health Sciences Center Communications Office at Emory. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|