|

Next-Door Neighbors

The built environment In Olmsted’s time, environmental health and urban design were intrinsically linked. But in the years since, their paths have diverged. Only recently has a movement emerged that again considers the relationship between health and place as a crucial element in designing communities. Known as “the built environment,” this approach ranges from small scale––how to build structures that promote health––to much larger scale––how to design communities that allocate land for green space with roads that are safe for pedestrians and bikes. This user-friendly design has myriad benefits: fewer cars result in decreased pollution. Better air may decrease asthma attacks. More walkers mean less obesity and better cardiac health. The transition from drivers to walkers eliminates road rage and improves mental health.

Jackson and Frumkin have worked together with other colleagues at CDC and elsewhere to define and articulate the theories of the built environment. They developed a research agenda for the NCEH based on the theories. In September 2003, Jackson—with Frumkin’s assistance—guest edited a special issue of the American Journal of Public Health, which explores the ideas behind the built environment. They are co-authors with Larry Frank, a landscape architect in Vancouver, of Urban Sprawl and Public Health, to be published in the spring. Frumkin and Jackson also worked with a CDC team to create a website that articulates the interaction between people and their environments and the effect on health ( www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/). The interlinking relationships between people and the environment mirror the collaboration of Frumkin and Jackson itself. Jackson teaches at RSPH as an adjunct faculty member, and Frumkin presents new scholarship on the built environment to senior-level staff at CDC. They share slides and take turns presenting their concepts to groups such as the National Governor’s Association, the American Institute of Architects, and the Surface Transportation Policy Project in Washington, D.C. Of their efforts to reconnect design, policy, the environment, and health, Olmsted would approve.

A roadmap to genetics

One current research focus of the office is the role of family history in public health. “We estimate that 30% to 50% of the population have a family history for the big three—cancer, heart disease, or diabetes. Yet family history is used to target only a small fraction of the population for health risks. Currently our public health approach to disease prevention is slanted toward one size fits all: Exercise, don’t smoke, and stay away from the sun. But if we could personalize prevention messages, we could achieve our overall goals of disease prevention.” To substantiate the hypothesis, CDC is funding a national clinical trial that will give a standard prevention message to a randomized group and a personalized message to other participants. The goal is to determine whether informing people of the implications of family history will affect changes in behavior. Khoury is keen to develop the genomics workforce of the future, and teaching at RSPH gives him a platform for recruitment. In 1989, when he first taught at Emory, his course earned students only one credit. Today, it merits three. “At first, only the brave would venture into the class,” Khoury says. “They are still afraid of the subject, but they realize they need to know some genetics and molecular biology to practice public health. I teach them how to apply epidemiological principles to genomics.” “I stay connected to Emory because of my love for teaching and interacting with the students,” he says. “If I can get one a year interested in genomics, I’ll be happy.”

Communicating to communities

Jorgensen brings a background in applied research, particularly the use of theory in message design, to RSPH, where she is an adjunct professor and award-winning teacher in the Department of Behavioral Science and Health Education. “I teach the way I would have wanted to learn the material as a student, with an eye to the useful and practical,” she says. “There’s nothing so practical as a good theory. Theories are like toolboxes. You pick the right tool for the problem at hand.” In a recent article in Lancet, she applied the theoretical principles of behavior to sun protection. “Changing human behavior is not easy, as all those involved in health prevention know,” she writes. “The more complex the behavior, the more difficult it is to change.” Jorgensen argues that sun protection is one of those complex behaviors, requiring support, education, and reinforcement from all aspects of society: families, healthcare systems, schools, and the mass media. “Behavioral change takes time and persistence,” she concludes. At the time Jorgensen did her own training, there were no tailor-made courses for those interested in a career in public health communication. She cobbled together a master’s degree in health communication at Boston University by creating her own curriculum out of courses in medicine, public health, and communications. At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, she followed her doctorate in health behavior and education with an extra year of coursework in journalism. In Jorgensen’s risk and health communication classes, students learn the process of developing a communications campaign from beginning to end. They consider the following: What is known about the disease? What are the existing educational materials? Where does theory guide the message? How can they incorporate what consumers know and change behavior? What channels do they choose to deliver the message? Richard Goodman, another CDC staff member who is an adjunct professor in the departments of Epidemiology and International Health, also brings the practical to his class on the principles of public health communication. In a recent class, he gave students a brief surveillance report from CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, which he formerly served as editor. Their assignment: working in small groups, they were to develop a message based on the data for specific audiences, including religious leaders, health care practitioners, and state legislators. The topic: sexual behavior among high-school students.

RSPH students get a first-hand look as Goodman forges into this new territory by interning in his office and working at conferences. During the past two summers, the Public Health Law Program has organized national conferences attended by some 500 practitioners from health departments, lawyers, and state legislators. One conference even led to the formation of the Public Health Law Association in 2003.

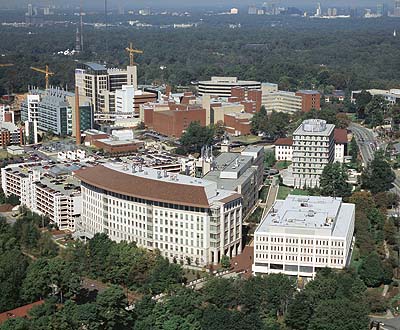

An environment for teaching

At RSPH, Williamson teaches a course in generalized linear models. His connection to the school was a natural transition after completing a post-doc there in 1996. He also holds an ScD from Harvard. “It is very rewarding to get to work with students,” Williamson says. “For me, teaching the same course has the benefit of my continuing to learn the material better.” He believes attendance at department seminars, collaboration on research papers with the faculty, and work on doctoral committees expands his general knowledge of biostatistics and rounds out his specialized research focus.

White notes that her course on environmental and occupational epidemiology is similar in many ways to one she and Howard Frumkin took in graduate school, where she earned an ScD. Her class reviews the literature and basic principles of study design, sources of bias, and interpretation of results, while guest lecturers bring practical research experience to the class. The goal of the course is to provide students with the knowledge and skills they need to independently and thoughtfully evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of an epidemiologic study. White recruits many of her colleagues at CDC and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry to teach in the course. They come from cancer epidemiology, environmental health, occupational health, disease surveillance, and other areas, bringing real-world insights to the students. The convergence of these fields in one class—for that matter in one school, in one neighborhood—is the rule rather than the exception in this community for public health.

Copyright © Emory University, 2003. All Rights

Reserved. |