|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

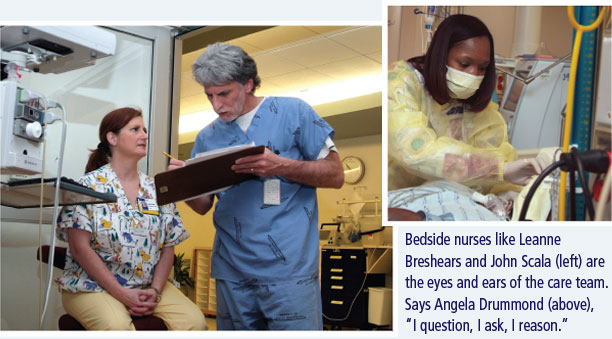

While

having families in the neuro ICU improves patient outcomes, it presents

additional challenges for delivering care for nurses like John Scala,

who has worked in neurocritical care for seven years. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

E-mail

to a Friend

E-mail

to a Friend  Printer Friendly

Printer Friendly |

|

| |

|

|

|

It

was not the same woman that Jason Forche saw lying in the bed in

room 52. One moment Sally R.* was alert and talking. She knew her

name and that she was in Emory University Hospital. A 39-year-old

mother of two, Sally was glad her husband was with her.

The

next moment—just 30 seconds later—Forche, the nurse

responsible for Sally’s care, knew something dramatic had

happened. None of the vividly colored monitors surrounding the bed

had blinked, changed their readouts, or uttered a peep. Everything

seemed the same except Sally had stopped talking to her husband.

To the untrained eye, that would mean

little, but in a neurointensive care unit that treats brain injuries,

nurses are keenly aware of any sign that suggests something is amiss.

Quickly, Forche called the nurse practitioner

in the unit, explained what he had checked and what he thought had

happened, and together they rushed Sally to the diagnostic CT machine

down the hall. The scan was negative. Forche then whisked her downstairs

for an angiogram, and as he feared, Sally was experiencing a cerebral

vasospasm, a potentially lethal constriction of a brain artery.

It had clenched shut, depriving parts of her brain of blood and

oxygen. A quick infusion of strong drugs reopened the vessel.

Sally was back. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

*

Her name has been changed to protect her privacy |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Welcome

to 2D ICU, a unit unlike any others at Emory,

or like few in the United States. In both form and function, it

is a place where physicians, nurses, and staff are applying an emerging

model of hospital care.

Here families stay with patients 24/7,

if they like, and clinical care is led by neuro intensivists, a

relatively new breed of MDs who specialize in treating critically

ill patients with brain injuries.

And it is on 2D ICU that nurses are

migrating from the monolithic central nursing station found on most

modern hospital floors back to patient rooms, to be as close to

the bedside as possible—the place where nursing care is traditionally

valued.

Accompanying this transition, these

nurses also are assuming bigger responsibilities. They are providing

input into how patients should be managed as well as what should

occur in a crisis. They are drawing on the newest technology to

provide smoother, coordinated care. They are encouraged to move

up the professional ladder and earn additional certification—and

many do. And in an even bigger way than in the past, they are proving

an indispensable resource not only to patients and their families

but also to the entire clinical team.

“Nurses are more than my eyes

and ears. They are my eyes, ears, mouth, hands, everything,”

says Owen Samuels, medical director of the neuroscience ICU program.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Convergence

of forces

The building of 2D ICU represents a convergence of medical, cultural,

and market forces at play in health care, changes that help explain

transformations in hospital nursing.

Foremost among them is that some hospitals

are morphing into a collection of critical care units that treat

the sickest of the sick. Emory Hospital, because of its tertiary-care

status and the breadth of specialties operating here, has long been

one of those facilities with a burgeoning critical care census.

At the same time, because of new national

restrictions on the number of hours that residents and interns can

work, there are fewer residents on the units to treat patients than

before. The traditional resident-fellow-attending academic model

has become strained, and nursing shortages and a dearth of critical

care specialists have plagued hospitals not only in the Emory system

but also across the country.

Simultaneously, health care consumers

have become savvier, more willing to choose a hospital based on

rankings in popular surveys, and on other criteria more akin to

a shopping mall experience—the look and feel of the place,

the customer service.

Even as the Emory neuro ICU was dealing

with these changes, it was growing fast. From a single seven-bed

unit in 1998, Emory’s neurocritical care has expanded now

to include almost five times as many beds in three units. Occupancy

now averages more than 90%, says Ray Quintero, department director

of 2D ICU.

One of the reasons for the rapid development

of the service is that patients are surviving catastrophic brain

injuries thanks to quicker, more advanced treatment. Another is

that many patients are referred here for procedures that are unavailable

elsewhere.

For example, Emory is one of the few

hospitals in the Southeast to offer a less invasive treatment for

aneurysms, or life-threatening bulges in brain blood vessels. This

technique involves threading a catheter through the patient’s

groin up into the brain, and depositing a tiny coil in the bulge

to block blood from entering. More typical treatment for an aneurysm

involves use of a titanium clip to bind the bulge, which first requires

a craniotomy to remove part of the skull.

While placement of the coil is less

invasive, it requires a huge amount of technology in the care of

these patients. And because complications may arise one or two weeks

after coiling or clipping, such treatments require one of the longest

hospital stays of any disorders, Quintero says. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

When

nurses practice

Long before 2D ICU was built, Samuels saw how these long stays combined

with resident shortages could damage the quality of care delivered

in the ICU. He turned to mid-level caregivers, what are known as

physician extenders, to fill the “care gap.” These physician

extenders include physician assistants, surgical assistants, nurse

anesthetists, and nurse practitioners (NPs).

NPs are registered nurses who have

completed advanced education and rigorous training in the diagnosis

and management of illnesses. As such, they are able to provide a

broad range of health care services.

On the neuro ICU, “they do all

sorts of complex, high-risk procedures, which would have been unheard

of years before,” Samuels says. Among them are placement of

invasive centralized arterial lines and pulmonary artery catheters

as well as lumbar punctures and drains.

Since NPs stay in the units during

day shifts (with plans to expand coverage to 24/7), they work hand

in glove with physicians, the care team, and, of course, bedside

nurses. The partnership between NPs and bedside nurses is important,

says NP Michelle Ossmann. “Bedside nursing is key,”

she says. “The nurses determine everything, including when

we take action. I can’t function without them.”

As NPs increasingly were given authority

in neurocritical care and as the number of beds and the services

grew, responsibilities also grew for experienced bedside nurses.

With patient safety as the top priority, they have the power to

stop care if they feel uncertain about a process.

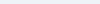

“We are more empowered to make

a change,” says Angela Drummond, who has worked in the unit

since 1999. “I question, I ask, I reason.”

Yet through all this increased responsibility

and empowerment, the element that can’t be diminished happens

at the bedside. It is the human touch. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Families

in shock

The tragedy that unfolds daily in the neuro ICU underscores the

fact that anyone can suffer a sudden and devastating neurologic

event. The disorders treated here are not the exclusive province

of the elderly.

“A man can say goodbye to his

family in the morning and unexpectedly be in our unit in the evening,”

says John Scala, who has worked in neurocritical care for seven

years. “Families are often in shock and grief because of the

abruptness of this illness.”

His point was made when, as the night

nurse in charge, he rounded on patients in 2D ICU. On this typical

evening, the patient mix included a woman in her 30s with a cranial

bleed caused by taking ten tablets of ephedra a day to lose weight;

a 31-year-old man in a coma from a steroid-induced stroke; and seven

patients, aged 39 to 72, recovering from aneurysm treatment.

In older models for delivering intensive

care, families in shock huddled together outside the intensive care

unit and were asked to refrain from intruding when the medical team

held rounds to discuss patient care and prognosis. The scenario

was less than ideal, says Samuels.

“Medicine and nursing have become

so complex and so demanding that it has taken both nurses and doctors

farther and farther from the patient’s bedside, both physically

and metaphorically,” says Samuels. “There is less hand-holding,

less hands-on touching, healing, and bonding with patients.”

When Emory administrators decided

in 2005 to expand the busy neuro ICU, Samuels put together a team

of nurses, neurologists, pharmacists, social workers, design experts,

and family members of former patients to figure out how to move

caregivers back to the bedside.

“I think it’s a mistake

to view families as yet another sort of checklist for the doctors

and the nurses to take care of,” Samuels says. “Medicine

in general has neglected the powerful and important role that families

and patients can play in the healing process.”

So the team set about to design a

unit “where the family and the patient are not objects of

treatment but are full participants in the whole healing process,”

he says. And that meant that nurses and families, too, returned

to the bedside. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Like

mother, like daughter

In June Sharkey’s experience, the nursing profession

is “completely different now” from when she first

stood by a patient’s bed in a small Mississippi hospital

in 1979. “If a doctor came into the room and you were

sitting down, you got up and gave him the chair,” she

says. “Nurses were no more than handmaidens to the doctors.”

It wasn’t much better

at Emory when she came in 1980 to work on a seven-bed special

care unit for neurology patients and a few overflow heart

patients. Nurses had little say in how the unit was operated

or patients were managed. “It was more like a dictatorship

than a democracy,” says Sharkey (above,

right). “The staff nurses did what the ranks above them

told them to do.”

Yet in 2006 when June’s

22-year-old daughter, April Sharkey (above,

left), joined Emory as a nurse in the same unit as her mother,

she entered a dramatically different environment. The younger

Sharkey’s experience of nursing is as “the patient’s

advocate,” she says.

The change in scenario began

to unfold about 10 years ago for nurses in the neuro ICU when

they first were invited to attend leadership meetings. There,

nurses have come into their own in a way that is still atypical

in other hospitals, both Sharkeys say. For example, June Sharkey

now can do such things as manage drug titration if a patient’s

status changes. “Our autonomy has increased,”

she says. “The majority of doctors here are open to

my input.”

In this new climate, nurses

also are pushed to do more, she says. “The patients

are sicker, and there is more technology to help us monitor

them. We have many more responsibilities in addition to the

typical bedside duties.”

April Sharkey, who received

her nursing degree from Emory less than two months before

she started working in 2D ICU, finds neurology to be a challenging

area for nursing. “You have to keep up with the research,”

she says. “I can’t believe how much I learn every

day, and after a 12-hour shift, I feel I have made a difference

in someone’s life.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Fine-tuning

form

There is no other critical care unit like 2D ICU in Atlanta, and

few in the country. Its form has helped further define the function

of the patient care team.

Patient-centered care is not new in

Emory Hospitals. The hospital care teams have followed the philosophy

for years, but they have been hampered by the design of the physical

plant. By contrast, 2D ICU, which opened in February, features a

new design tailored for 21st-century health care. Among its features

are a large waiting area for family members, with a kitchenette

and a children’s play area on one side. Like a hotel concierge,

two assistants take turns staffing a welcome desk, offering solace

along with towels for the shower room or soap for the washer and

dryer. Within each patient room is a separate studio area for family

members, with chairs that open into beds. Soon, the suites will

have laptop computers.

When not at the bedside or in treatment

areas, nurses work from alcoves situated between patient rooms.

They have only to glance in to see and hear the patients and to

monitor IV fluids and a myriad of machines. Often, a probe is embedded

into the brain to measure temperature, oxygen, and intracranial pressure, and transcranial Doppler ultrasound is

available to look at the velocity of blood flow. A CT scanner is

just steps away.

and intracranial pressure, and transcranial Doppler ultrasound is

available to look at the velocity of blood flow. A CT scanner is

just steps away.

Families come and go and are welcome

to talk with physicians and nurses during rounds. Their presence

has put nurses front and center to answer questions and provide

information. Quintero sees this change as positive, emphasizing

the needs of the patient before those of the medical team.

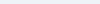

To create an environment where nurses

become invested and can contribute the most, Quintero has turned

to the nurses themselves. “I tell them, it’s not my

unit. It’s your unit.” Creation of 2D ICU involved shared

decision-making, a process that sent a team of nurses across the

country to search for the perfect equipment boom for the patient

rooms, among other tasks.

“I was amazed that I was asked

to go,” says June Sharkey, who has worked as a nurse for 27

years. “They listened to what I had to say about one of the

most costly decisions to be made in the unit.”

“I know what nurses need because

I am a clinical nurse too,” says Quintero, who has 25 years

of hands-on nursing experience, including 20 years as military nurse

in Texas at the Air Force’s largest hospital.

However, changes in the environment

may have unknown consequences for nurses, says John Scala. “Until

you build it and live in it, you don’t know how it works,”

he says. “We work at a high stress level anyway, but now we

have to explain everything we are doing to everyone and act as both

educator and psychologist. The thing that makes it okay is that

we all know it is the right thing to do.”

The adjustment can take some time.

“It was difficult at first,” says Angel Sostre, a nurse

and the day shift clinical manager. Recently Sostre came from a

trauma ICU in Miami, where he learned to work fast and on his own.

“Having family around when I want to do procedures took an

adjustment on my part. I felt I was crowding them,” he says.

“But once they build a trust in me, the family will let me

do my job. It works as long as we understand the roles each of us

plays.”

Everyone in 2D ICU is adjusting, figuring

out what works and what doesn’t, and where the limit exists

for just how much nurses can do, says Samuels.

“In trying to establish a new

standard for providing care for these critically ill patients and

their families, we are all pushing the envelope,” Samuels

says. “Creating this new culture doesn’t have a beginning

and an end: it’s a process, and it’s an extremely challenging

one at that.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

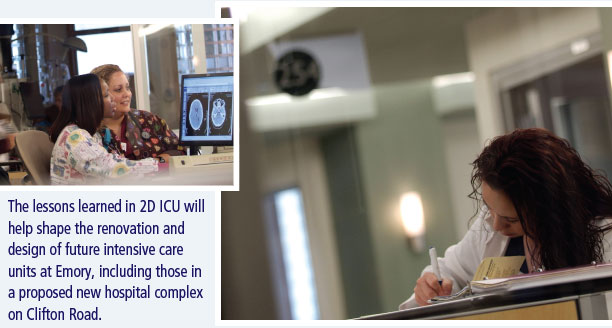

Taking

it to the next level

In a sense, 2D ICU is a demonstration unit that is transforming

the culture of patient care, says Susan Grant, chief nursing officer

for Emory Healthcare. The lessons learned here will help shape the

form that future intensive care units in the proposed new Emory

Hospital complex will take.

“Having family members in a

unit 24/7 changes clinical practices, challenging the old way of

doing things,” says Grant. “It is not a small thing.”

But just as family-centered health

care, along with new technology and better designed physical space,

improves outcomes, so does the evolution of nursing practice.

Grant herself began her professional

career as a bedside nurse at Emory. In the 20 years since, as a

nurse and nursing administrator serving in educational institutions

across the United States, she has witnessed firsthand the changing

profession. “We are far beyond Florence Nightingale’s

day, for sure, but we have gone miles beyond what nursing was even

five years ago,” she says. The professional practice of nursing

now is responding to and being proactive around technology, research,

medical advancement, reimbursements, regulations, risk aversion,

and disease management, Grant says. Nursing as a discipline needs

especially to be more central to the health care administrative

process.

For all those reasons, Grant is taking

nurses throughout Emory Healthcare on the kind of progressive journey

that neurocritical care has navigated. She is seeking to have the

entire Emory Healthcare system awarded “magnet” recognition,

bestowed by the American Nurses Credentialing Center. Magnet status

is exceedingly hard to come by. Only 11 health care systems have

been so designated since the program began more than 20 years ago.

Only 4% of U.S. hospitals—238 out of 5,764—have earned

these credentials, which may take up to seven years.

The magnet program is designed to

provide consumers with the ultimate benchmark by which to measure

the quality of care offered by nurses, and by extension, their institution.

“This is not window dressing. High nursing standards really

improve patient care,” says Grant, who in a previous position

led the University of Washington Medical Center through two renewals

of credentialing for the magnet program.

“In many ways, issues of patient

safety have really forced this movement,” Grant says. “To

address them, health care is learning a lot from aviation and other

high-risk industries. To ensure safe flight, everyone on the flight

team—not just the pilot—has to be able to say something

is not right when it deviates from the routine standard of care.”

Emory Healthcare has already instituted

a “shared decision making” structure across its system

to include input from workers at all levels as well as from families.

And on the floors, nurses are engaged in “unit practice councils”

that identify practices that could be improved and then determine

how to make that happen.

Angela Drummond leads the effort in

the neuro ICU. The 13-member council has identified bloodstream

infections and

ventilator-associated pneumonia as two areas of concern. Nurses

have researched the existing rates, matched these to national averages—“too

high,” Drummond says—and are now seeking ways to lower

the incidence. In the space of just two meetings, they have found

that two very low-cost yet high impact solutions will help:

proper hand-washing on the part of all clinical staff and mouth

care for patients every four hours.

“This encourages nurses to practice

evidence-based nursing, and we are all excited about it,”

Drummond says. “We are working hard to get the number of those

infections down, which will improve outcomes.”

Magnet designation also comes when

nurses develop professionally, and on that score, Emory has a good

leg to stand on, says Grant, who also serves as the first assistant

dean for clinical leadership at the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School

of Nursing.

“As far as nursing education

goes, you can do anything at Emory Healthcare,” Drummond says.

The neurocritical care nurses seem

to take that slogan to heart. Of the 87 registered nurses working

in the three ICUs, nine are taking graduate courses, and six are

studying to be nurse practitioners.

Ironically, a commitment to staff

advancement also has the potential to create rapid turnover in nurses

and even shortages—the very thing professional development

is supposed to bring to an end, says Sharkey, who spends a lot of

her time training new nurses.

Part of the challenge on this frontier

of transforming health and healing, then, is to balance new empowerment

and knowledge for nurses with the traditional hands-on care they

deliver at the bedside. That will create the strongest kind of magnet

for patients and nurses alike.

“This is a more humanized kind

of health care,” Drummond says. “The feeling now is

that we are all in this together.”

Videos

about the neuro ICU

Renee

Twombly is a freelancer who writes frequently on health care topics. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|