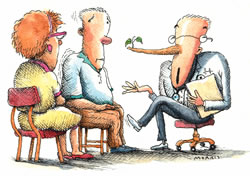

"Well on the surface and to the unpracticed eye, it may LOOK like he received 10 times the appropriate dose, but . . ."

The health professional who dodges patient or family questions about medical errors may be taking a huge liability risk.

John Banja is a clinical ethicist at the Center for Ethics at Emory. He is currently working on a research grant awarded to the Georgia Hospital Association from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality on developing model practices for disclosing medical errors. He can be reached at 404-712-4804 or jbanja@emory.edu.

The advice traditionally offered by defense lawyers and malpractice insurance companies - don't say "error" or "mistake" and do not apologize - may cause more costly lawsuits than it prevents.

In this issue

From the CEO / LettersPromises writ in stone

Taking care of people

Taming the obNOXious enzyme

Moving forward

Noteworthy

On Point:

Communicating medical errors

by John Banja

Shock, horror, guilt, shame, feelings of incompetence

and betrayal of the patient, and terror over a potential lawsuit --

all are documented and entirely understandable reactions from health

professionals who have committed serious, harm-causing medical errors.

Often these feelings never go away.

Studies of nurses and physicians demonstrate how such feelings recur (often with amazing intensity) when health professionals recall and talk about their errors. Of course, these feelings are precisely the ones health professionals should have after committing a serious error. Physicians or nurses who are unmoved or blasť about their errors would hardly seem the ones you or I would want treating us.

Unfortunately, such anguished feelings discourage many (but certainly not all) health professionals from disclosing errors to harmed patients or their families. Because they are so painful, these feelings tend to trigger the health professional's psychological defenses and coping mechanisms, which are naturally geared to preserving and protecting us and to relieving our emotional or physical pain.

Although recent research indicates that health professionals are increasingly willing to disclose errors to the persons they have harmed, many errors remain concealed. Plenty of anecdotal evidence indicates how health professionals rationalize concealing an error ("Telling the family about this error will only make them feel worse"). Or excuse the error ("Well, yes, the patient shouldn't have received 10 times the medication dose that was ordered, but we are so short staffed that these things are occasionally going to happen"). Or shift blame, sometimes to the patient ("If the patient had taken better care of himself, the harm from the error wouldn't have been so bad").

Needless to say, none of these psychological ploys complies with section 8.12 of the American Medical Association's Current Opinion on the Code of Medical Ethics, which states the following:

It is a fundamental ethical requirement that a physician should at all times deal honestly and openly with patients. Patients have a right to know their past and present medical status and to be free of any mistaken beliefs concerning their conditions. Situations occasionally occur in which a patient suffers significant medical complications that may have resulted from the physician's mistake or judgment. In these situations, the physician is ethically required to inform the patient of all the facts necessary to ensure understanding of what has occurred.... Concern regarding legal liability which might result following truthful disclosure should not affect the physician's honesty with a patient.

In the face of serious, harm-causing errors, though, many physicians find ethical exhortations easier said than done. But there is another reason beside the ethical one that should increasingly encourage error disclosure, and it is exquisitely linked with those self-preserving instincts that seem to discourage it initially. It is this:

A growing body of literature indicates that harmed patients and their families naturally are suspicious when something goes wrong, especially if they initially were led to believe that the procedure or their hospital stay would be uneventful. When something dreadful happens (either related or unrelated to error), the harmed parties naturally want to know what happened, and they ask questions.

The health professional who dodges these questions, who remains distant or uncommunicative, who uses medical jargon to cover up the situation, or who simply doesn't answer the patient's or family's questions in a truthful, caring, and comprehensive way may be taking a huge liability risk. He or she may be oblivious to the way the patient or family is paying keen attention to everything that is said as well as to the body language of the communicators.

In one malpractice case that I have some familiarity with, a family member said in effect, "We knew immediately that the surgeon and anesthesiologist were not telling us everything they knew. The surgeon never directly answered our questions, and we kept going around and around for 20 minutes. The anesthesiologist just stood there and looked down at the floor most of the time."

What I am suggesting is that in instances in which the health professional knows that he or she has committed a serious, harm-causing error, the advice traditionally offered by defense lawyers and malpractice insurance companies - don't say "error" or "mistake" and do not apologize - is not only unethical, but it may very well cause more costly lawsuits than it prevents.

What health professionals must learn to do is reorient their feelings about medical error: from anxiety connected to disclosure to anxiety connected to nondisclosure. Here is one more thing to consider. It comes from the psychological literature on forgiveness. A fairly consistent finding from victim-offender research is that offenders tend to minimize, rationalize, or dilute the impact of their offense. If Jack and Jill commit exactly the same offense with exactly the same repercussions, Jack is more likely to excuse his offense but be "objective" about Jill's offense, while Jill will be more dismissive of her offense than she will of Jack's. Victims, however, respond just the opposite. If the offense goes without acknowledgement, explanation, or apology, victims will often obsess on what happened, which may cause the impact of the harm to seem worse and worse upon each iteration.

By acknowledging the offense, apologizing, and even requesting forgiveness - which is hard for the offender to do because his or her psychological defenses may dictate the opposite - the offender keeps the victim's harm experience from psychologically spiraling into bitterness and sadistic rage.

Plaintiff lawyers know this all too well. They are accustomed to counseling angry clients who feel dishonored, dismissed, and disrespected by a health professional's failure to communicate in a supportive and truthful way. Of course, that compassionate and truthful error disclosure might be immensely difficult for a health professional to do.

Yet, as Neil Galatz, a prominent Las Vegas attorney recently told an audience of physicians, "Your first loss is your cheapest loss." Doing the right thing and doing it well at the earliest opportunity isn't only ethical: it can prevent huge professional, personal, and financial losses from materializing downstream."

What's your opinion? If you are interested in submitting an editorial

regarding an issue vital to the well-being of the Woodruff Health Sciences

Center and the people it serves, send your proposal to Momentum,

1440 Clifton Road, Suite 105, Atlanta, GA 30322; call 404-727-8793;

or e-mail mgoldma@emory.edu.

Copyright © Emory University, 2003. All Rights Reserved.

Send comments to the Editors.

Web version by Jaime Henriquez.