The first thing we all noticed was the flying chalk.

As white flakes cascaded to the floor, we decided we had never seen anyone write so fast on a blackboard. And then we watched the intensity, the focus—and the joy—of this bustling, faintly smiling, diminutive woman as she unraveled the molecular mysteries of the B vitamins. Immersed as we were in the murky amino acid soup of biochemistry in 1954, we suddenly encountered something charming in lipothiamine pyrophosphate, something dramatic in niacin deficiency. Pressed, muddled, and slightly fearful, like most freshman medical students, we now began to form a new vision: We wanted to become engaged, vivacious, passionate. In other words, we wanted to be Dr. Evangeline T. Papageorge.

In this

little exercise this amazing teacher had not, you understand, broadcast

her seeds of wisdom wastefully upon a parched plain. She had first plowed

the soil, tilled it—titillated it. Now even ordinary data would germinate

vigorously in our newly galvanized young minds.

This was

my first exposure to The Evangeline Effect. The next occurred when, walking

with her across the tiny quadrangle between Anatomy and Physiology, she

outlined to me her original PhD project. Her pace, already brisk, quickened;

and her voice, already animated, heightened as she went into transport

over the genetic defect of 2 phenylketonuria. I learned something, of

course, but now mainly I wanted to rededicate my life to genetics.

Another

stanza of The Effect appeared at midyear. One of our classmates was discovered

one night sitting in a corner of a classroom—catatonic. Later, as

he received inpatient therapy for what was feared to represent emerging

schizophrenia, Dr. Papageorge left her lab and her podium and her office

to visit the parents at their home. Evangeline, the teacher, the administrator,

the researcher, had adopted still another role—cheerleader.

Her myriad

faculty assignments included from time to time the admissions committee.

One candidate had applied after a Vietnam tour complicated by an arduous

period as a POW. A committee member suggested a psychiatric exam in view

of the emotional trauma the student had experienced.

Evangeline

said, “Why then we’ll have to give everybody a psych exam, won’t

we, maybe (with a wistful smile) including the faculty.” Then, gazing

into some distant space, she stood, drawing herself up to her full five

feet, pounded the table gently, and said: “Ladies and gentlemen,

this student is the only one in this medical school who has had a psych

exam. . .and he passed with flying colors.”

The student

was admitted and eventually elected president of the senior class.

Medical

students of course were always having problems: fatigue, grade trouble,

distress at home, conflicts with teachers, and just plain confusion. Somehow

they all seemed to end up in Evangeline’s office. She would reward

them with endless patience, intuition, empathy, but unshakable high expectations.

She did not forgive; she empowered. She did not pass out handkerchiefs;

she created tools. Her warmth was lined with iron. She was fire and ice.

Some years

ago, our Medical Alumni Executive Committee felt the educational

function was being distracted by other concerns and decided to create

a fund to recognize the best teacher each year, including a significant

cash award, like a mini Nobel Prize. Evangeline was invited to attend

a session to discuss the project with us and the top brass of the medical

faculty. At one point, a high official of the medical school expressed

doubt. He said we can quantitate research, we can count publications,

we can add up clinical productivity, but the teaching function is tough

to evaluate.

“In

promotions committee,” he said, “they describe everybody as

‘a great teacher.’ It’s too subjective. We can’t really

identify the best educators.”

“If

it is true that we can’t identify the top teachers,” said Evangeline,

with a spreading rueful grin, “how is it that right now all of us

in this room (she made a broad, even imperious gesture) know who they

are? Don’t we?”

The Award

happened and was named for—guess who—Evangeline. It is now informally

called the Papageorge Prize. Funded by alumni contributions, it continues

to approach its original goal of $1 million and spins off a significant

reward each year, complete with appropriate academic reverberations, to

the teacher identified as most outstanding by students and peers.

The last

time I saw Evangeline, she was hospitalized at Emory with bilateral pneumonia.

Lying in her bed, managing to be radiant, she extended her arms for a

hug, reassuring me with a smile that cultures had shown she was not contagious.

Sick and 93, she asked about my wife, by name, and about my son, her one-time

student, calling him “Billy.” She told me to advise him to keep

up his interest in statistics and his overall dedication.

Funerals

of people aged 94 are generally poorly attended because all their contemporaries

are gone. But at the Greek Orthodox Church on Clairmont Road on a Tuesday

afternoon last September, even standing room was at a premium. The Evangeline

Effect was still in force.

And that

is likely to continue. Boyle’s Law is easy to recite. Avogadro’s

Number is a specific quantity. Even the Heisenberg Principle can be enunciated.

All these concepts live on after their creators are gone; so with The

Evangeline Effect. But let’s see: What is it? There’s the focus,

the smile, the intensity, the caring patience, the unerring probity. It’s

hard to define. But then we all know what it is. Don’t we?

William C. Waters III, 58M, a long-time volunteer faculty member at Emory, past president of the Medical Alumni Association, and former Emory Medalist, helped create the Papageorge Teaching Award. He also gave the Edgar Fincher Lecture at the Alpha Omega Alpha induction ceremony in March.

Copyright © Emory

University, 2004. All Rights Reserved

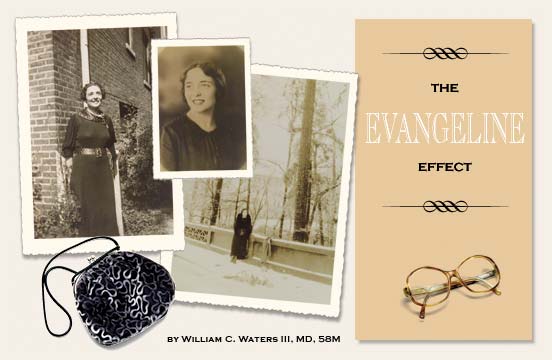

Evangeline

(top photo, second from right) with siblings. Middle photo: Evangeline

(left) in 1935 with brother George and Ann in Ann Arbor, where Evangeline

was completing her PhD in biochemistry at the University of Michigan.

She worked on her degree during summers and during a two-year leave from

Emory. Bottom photo: Evangeline (center) was named Atlanta’s Woman

of the Year in Education in 1952. She is surrounded by her mother (right)

and George

(left). Evangeline with Kyle Peterson, recipient of the Papageorge Teaching

Award in 1998. Bottom photo: Evangeline in January 2001, still beautiful

at 94.