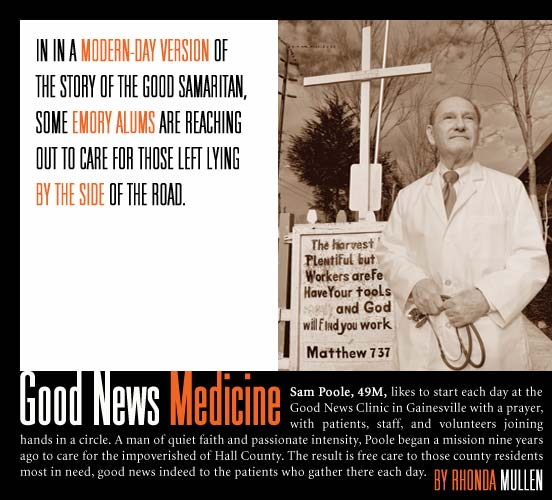

The way we learned medicine at Grady was that you help the indigent,”

says Poole, who says he finds helping those in need therapeutic for his

own health. “I’ve had two failed back operations, but when I’m

seeing these patients, it completely takes my mind off my back.”

Poole gives

credit for starting the Good News project to Susie Harris, his neighbor

and former nursing director at the Northeast Georgia Medical Center, where

he was director of cardiology until he retired. Harris and Poole go back

35 years. “The nurses at the hospital used to be a little afraid

of him,” Harris confides. “He’s a tough doctor, and he

always demanded their best. But he’s also a good doctor and a good

man.”

That mixture

made Poole just the person to lead a new medical mission in Gainesville.

In 1993, he and Harris first saw patients in cramped quarters at the Good

News Mission, treating patients in two small rooms meant to be closets.

By the end of 1994, the group had seen close to 4,000 patients, and they

went looking for better space.

In the search,

Poole discovered that the clinic would qualify for $600,000 in federal

aid, but he decided not to take it. “The money had not only strings

but also ropes and chains attached to it,” he says. “They wanted

us to move to a better part of town and see a better clientele, and they

wouldn’t let us start our day in the clinic with a prayer or devotional.”

Instead,

Poole found private support to renovate a glass works storage facility

next door to the mission. (Donor Ann Warren Thomas provided the “seed

money,” he says.)

Against an

industrial backdrop of aged warehouses, barbed wire fences, and a red-

and white-checked water tower, the Good News Clinic opened its doors in

1995. Here patients have access to free medical services, including primary

and specialist care. Ed Burnette, a 1961 graduate of Emory’s dental

school, directs the clinic’s dental arm, the Green Warren Dental

Clinic, named for Ann Thomas’s father.

Some 100

volunteers, 44 dentists, and 30 physicians (including 12 Emory alumni)

keep the clinic running each weekday and three nights a month. “Plus,

there are 50 doctors in town who will provide free consults,” says

Poole. The clinic has only four salaried employees—two nurses, a

dental assistant, and a full-time interpreter. In 2001, the clinic treated

about 10,000 people. (BACK

TO TOP)

About 65%

of these patients are Hispanic workers and their families—some 40%

employed in the Hall County poultry industry. In treating this group,

Poole finds the biggest challenge is changing lifestyle to control high

blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity.

One of his

more dramatic cases involved a middle-aged Hispanic man who was losing

strength in his legs and his hands. When the patient visited the Good

News Clinic, he was already too weak to continue working at the poultry

plant. Poole examined him and determined that he was headed toward paraplegia

if something wasn’t done soon. Poole recruited a neurosurgeon to

operate free of charge on two cervical disks pressing against the man’s

spinal column. Today, the man walks normally and is back at work.

The local

hospital even waived the charges for its services and, in fact, regularly

donates lab and radiology work to the clinic. This is in part because

of Poole’s advocacy and in part because it is good business. “In

this instance, the hospital had to eat a little bill,” Poole says,

“but in the end, the clinic saves them money. We keep people who

can’t pay out of the hospital. We can offer good care for folks inexpensively

because we are high touch and low tech. We see our patients often and

can take our time with them, and they don’t need so many fancy tests.

A long-term relationship with a doctor is a luxury most of these people

have never had.”

In addition

to free care, the clinic provides free medicine, most from doctors’

office samples. That practice has been complicated by recently tightened

FDA regulations. In fact, the clinic may soon join other free clinics

around the nation in fighting those regulations in court. “The FDA

doesn’t want us to give free medicine because it fears physicians

could make a mistake,” Poole says. “But free medicine is the

base of our care. If a person doesn’t have a cent to his name, he

can’t pay for medicine.”

Poole’s

efforts have received recognition and gratitude in Gainesville, where

the Rotary Club named him Man of the Year in 2001. He is uncomfortable

in the spotlight, however, and would rather deflect attention toward his

cause. He is convinced that free clinics are an important part of the

solution for indigent care, and he sees a great need for more of them

statewide. Neighboring states are far ahead of Georgia, with 36 free clinics

in North Carolina, 22 in South Carolina, 20 in Florida, and 32 in Virginia.

Poole is out to do something about that, encouraged by colleagues who

have developed free clinics elsewhere in the state. (BACK

TO TOP)

The word

has spread

Every Friday, volunteers at the Jasper Community Food Pantry package groceries

for more than 125 needy families in Pickens County. The pantry is based

at the Episcopal Church of the Holy Family, where John Spitznagel, professor

emeritus and former chair of microbiology at Emory School of Medicine,

is a member.

Many of the

clients of the food pantry have serious health problems, and their situation

got Spitznagel and others to thinking. “We heard one sad story after

another—single mothers trying to work and pay their bills, elderly

people choosing between buying food or medicine,” he says.

To learn

more about the extent of the need, he surveyed Jasper businesses and two

local hospital emergency rooms and consulted food pantry and census data.

He found that 14% of Pickens County residents live below the poverty level

and that half of all those eligible for Georgia’s Peachcare program

for children can’t afford the monthly co-pay.

Inspired

by Poole (with whom he served on the house staff at St. Louis’s Barnes

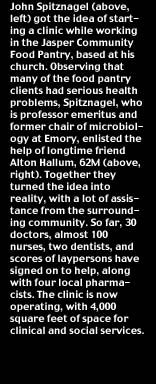

Hospital in the early 1950s), Spitznagel and his old friend Alton Hallum

Jr., 62M, decided to start a free clinic of their own. Thanks to dogged

persistence and hard work, the Good Samaritan Health and Wellness Center

opened in Jasper this spring.

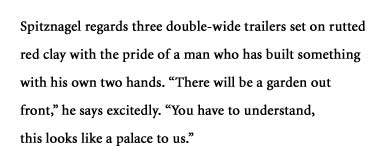

They’ve

had a lot of help. A volunteer grant writer raised money for equipment.

The Pickens County Commission donated land behind the county health department.

The commission and the mayor of Jasper donated a trailer, and the clinic

raised funds to buy two more. Volunteers renovated the space, which provides

4,000 square feet for clinical and social services.

To date,

30 physicians, almost 100 nurses, two dentists, and scores of laypeople

have signed on to help. Four local pharmacists have agreed to help provide

medicine, and the group has forged a working relationship with a local

hospital.

Spitznagel

is heartened at how the community has pulled together to care for the

indigent. Like Poole, he and Hallum believe that grassroot efforts can

succeed where federal programs have fallen short.

“Early

in my practice, there was no Medicare or Medicaid,” says Hallum.

“We told the affluent: ‘We need to charge you more to cover

the costs for those who can’t pay.’ Now, the standards for Medicaid

are tougher, and some 45 million people fall through the cracks.

“There

has to be a system like this to take care of people who can’t pay.

Our effort is run largely by retirees who want to give back. If everybody

pitches in, we can fill in the gaps, and we can do it better and more

efficiently than the government.” (BACK

TO TOP)

Those

with ears, let them hear

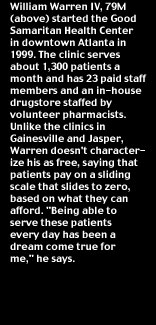

In 1995,

William Warren IV, 79M, traded in a successful pediatrics practice in

the Atlanta suburbs to establish his own medical practice for the working

poor and homeless in a no-man’s land downtown. “This was a way

to flesh out my Christianity,” says Warren, the great-great-grandson

of Coca-Cola founder Asa Candler. “The more I thought and prayed

about it, I found my calling was to the inner city.”

For three

years, Warren volunteered at several free clinics around Atlanta, working

at Techwood Baptist Center, the Mercy Mobile unit at Central Health in

Grant Park, and even venturing as far north as Gainesville once a week

to work alongside Sam Poole.

These were

training grounds for Warren, and by 1998, he had learned some important

lessons about what worked and what didn’t. For starters, he discovered

he needed his own place. His practice in the Baptist Center was limited

by space, and the health center there competed with other needs the church

was trying to meet. “You can’t do job training, provide clothing

and food, and dispense health care, all these little bits of things, all

at the same time. You end up doing none of them particularly well,”

says Warren.

Raising more

than $2 million, including money of his own, Warren renovated an old warehouse

to house his new clinic. The Good Samaritan Health Center sits north of

Centennial Olympic Park. Each weekday from 8:30 to 5, two doctors, two

nurse practitioners, two dentists, a counselor, support staff, and volunteers

serve patients in need. The working poor make up 65% of the practice,

and 10% of its patients qualify for Medicaid, which the clinic accepts.

Like his

counterparts in north Georgia, Warren prizes his clinic’s private

status and has little interest in federal aid with strings attached. (“This

is a Christian mission,” he says. “If I want to hang the Ten

Commandments on the wall, I can.”) Unlike the clinics in Gainesville

and Jasper, however, Warren doesn’t characterize his as free. ”We

have a different philosophy—that our patients want to pay what they

can afford and that they should. We have a sliding scale. But people who

can’t pay don’t.” Warren’s clinic is also the largest

of the three clinics, with 23 paid staff members. (BACK

TO TOP)

The patients

who come to the Good Samaritan—some 1,300 a month—hear about

the center by word of mouth and referrals from shelters and charitable

organizations. “Their medical and dental needs are the same as yours

or mine,” Warren says, “but their social needs are gargantuan.

They have so much life complication and baggage. They live from crisis

to crisis. If they’re hungry, they take care of that that day. If

they have an earache, they will take care of that. If they have high blood

pressure, well, that can wait.”

Warren recently

saw a 13-year-old diabetic who had gone without insulin for two weeks.

It took him two phone calls to reach her previous doctor to discuss her

medications, more time to check the clinic’s pharmaceutical stock,

and still more time to enroll the patient in a government assistance program

for diabetics.

Providing

medicine is essential to the practice, and an in-house drugstore, staffed

by volunteer pharmacists, dispenses drug samples. The clinic enrolls some

patients in programs offered by pharmaceutical companies for the poor.

If Medicaid, the samples, and the drug programs cannot meet a patient’s

needs, the clinic issues a medication voucher paid out of its operating

budget, about $1.1 million per year.

Despite the

many challenges inherent in operating such a clinic, Billy Warren, like

the other good news doctors, finds immense joy in this work. “It’s

true,” he says, “that ‘without a vision, the people perish.’

For me, being able to serve these patients every day, this is a dream

come true.”

Physicians

who would like to volunteer their time and service can call the following:

Good News

Clinic in Gainesville: 770-503-1369

Good Samaritan in Jasper: 706-579-1226

Good Samaritan in Atlanta: 404-523-6571, ext. 226

Rhonda Mullen is an Atlanta freelance writer.

Copyright © Emory

University, 2004. All Rights Reserved